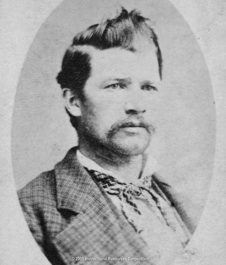

Denis Kearney was the most polarizing figure of the late 1870’s. His inflammatory rhetoric launched a political and social revolution in San Francisco. It also landed him in the San Francisco jail.

The 1870’s were a time of great turmoil in San Francisco. The Transcontinental railway had just been completed, leading to an influx of goods and supplies from the East Coast and the settlement of thousands of Chinese immigrants who had been a major labor force for the railroad construction.

In 1870, San Francisco’s population was 149,000. Of this number, Chinese immigrants numbered 12,000. There were over twice that number of Irish immigrants. By the end of the decade San Francisco’s population had grown to 234,000. A nationwide recession led to unemployment everywhere. Work that paid one dollar an hour in 1850 brought in only two dollars a day in 1875. Yet, San Francisco had also developed a super-wealthy community of millionaires who had made fortunes on the railroad and from the Nevada silver mines.

The great disparity in wealth gave birth to a short-lived political movement called The Workingmen’s Party of California. Its fiery leader was Denis Kearney.

The Workingmen’s Party was not a traditional labor party. It had its share of laborers, but it also embraced the small businessman. It organized around the complaint that a few rich men controlled the lives of everyone else and cheap Chinese labor stole the few remaining jobs.

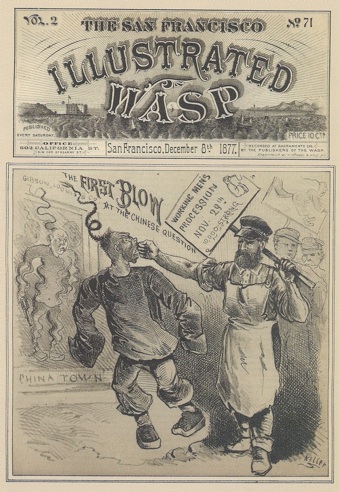

The WPC did not initiate the Anti-Chinese movement – it had been a political hotspot for years. For example, in 1873, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed the “Cubic Air Ordinance,” which required at least 500 cubic feet per person in any housing unit, and act directed at the crowded conditions in Chinatown. They also passed a law requiring the Sheriff to cut the hair of new prisoners (the Pigtail Ordinance, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pigtail_Ordinance ), designed primarily to cut off the queues of Chinese men.

Kearney was himself an immigrant from Ireland. He ran his own small business, a draying company. A dray is a small cart pulled by horses. In other words, he offered transport services.

Kearney was arrested a number of times for his incendiary speech. His first arrests in November 1877 resulted in a judge dismissing all charges because his speeches did not result in violence and the “incitement” law that he had violated had not been properly passed.

The San Francisco Board of Supervisors then passed a more thorough “gag” law, making it unlawful for any person by word, act, language or other means to induce others to commit any crime.

He was arrested again in January 1878 for inciting a riot. He stayed in jail for a month until he was acquitted in a jury trial.

After his initial arrests, Kearney concentrated on organizing a political movement which resulted in a sweep of municipal offices in the election of September 3, 1879. The Workingmen’s Party candidates won the office of Mayor, Sheriff (Tom Desmond), Auditor, Tax Collector, District Attorney and Treasurer. This was the high point for the WPC and the beginning of its decline.

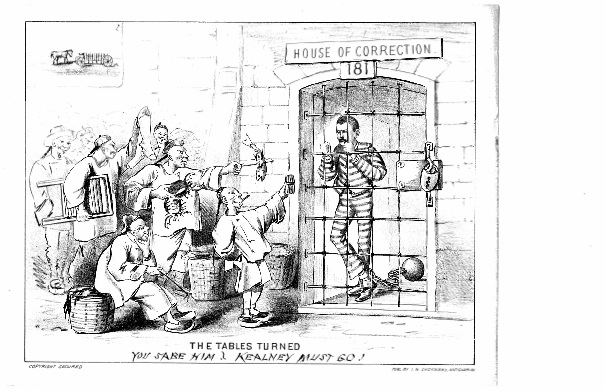

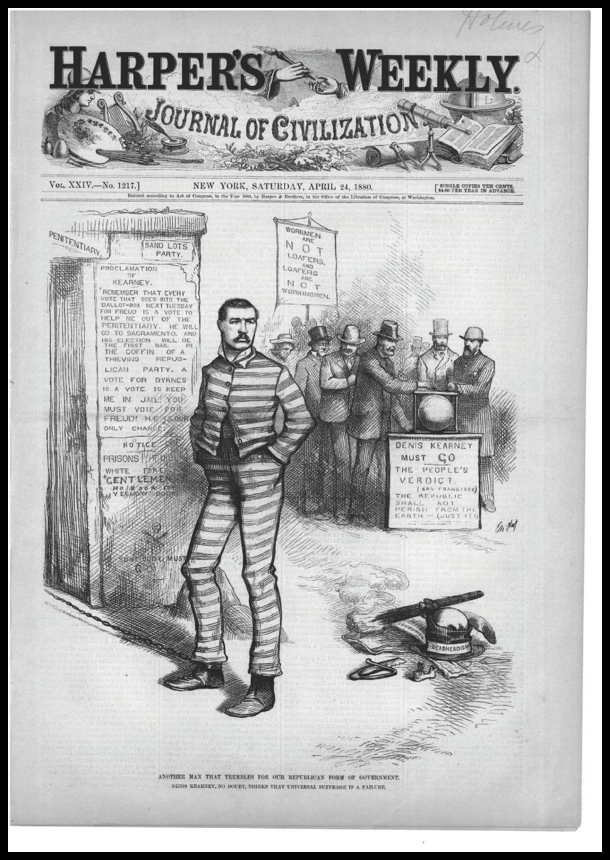

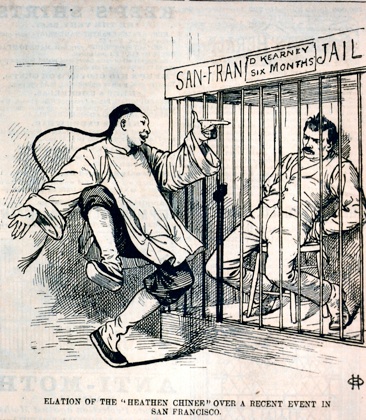

Kearney tried to rally the organization again in 1880, but he was again arrested for inflammatory speech and sentenced to six months in the county jail. This event was the subject of several great newspaper cartoons and even made news in The New York Times (March 12, 1880).

The Workingmen’s Party was all but gone by 1881. Sheriff Tom Desmond tried to start his own branch of the WPC and also joined the Democratic Party. It wasn’t enough for him to avoid defeat in the 1881 election, along with all of the other WPC candidates.

Denis Kearney faded from political favor quickly, although he entered the race for Sheriff in 1886. Out of about 44,000 votes cast in that race, Kearney received 333. (Examiner, 11-6-1886)

Kearney continued in business and obtained a measure of success. At the time of his death in 1907, he was wealthy enough that one of his daughters was visiting Paris, one was in Japan while on a world tour and the third was singing in Europe. (Shumsky, p. 56)

Sources and recommended reading:

The Evolution of Political Protest and The Workingmen’s Party of California, Neil Shumsky, Ohio State University Press, 1991.

The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and The Anti-Chinese Movement in California, Alexander Saxton, University of California Press, 1971.

California Clash: Irish and Chinese Labor in San Francisco, 1850-1870, Daniel J. Meissner, The Irish in the San Francisco Bay Area, Donald Jordan & Timothy O’Keefe, Editors, Irish Literay and Historical Society, San Francisco 2005.

The San Francisco Wasp: An Illustrated History. Richard S. West, Periodyssey Press, Easthampton, Mass., 2004.

Note on “Tables are Turned”: According to Richard West, by the mid 1870’s “San Francisco boasted 115 cigar making plants, employing nearly 6,000 workers, realizing $5,000,000 annually. Nearly all of the plants were Chinese owned and Chinese-staffed.” P. 20